30 Hours to Kathmandu

6 May ’20

“Look I’m telling you” Max warned “we can’t take the general sleeper class car. I had a guy show me a video he took while traveling in one of those and it looked completely miserable - the pervading background noise was one of human moaning and misery.”

“Well,” I responded “all the other tickets are gone. Your guy still hasn’t gotten back to us about the straight shot bus, so I’ll just book these as backup. They’re only five bucks a person anyways.”

“Hello. You are Maxwell, yes?” The Indian man was loud enough over the phone that I could hear him despite it not being on speaker. “Yeah that’s me” he responded casually. “The bus from Varanasi to Kathmandu will not be running tomorrow. Very sorry” the other side of the line continued. “Well what am I supposed to do now?” Max asked the phone, rhetorically. We both knew what this meant: a sleepless night in a moving box of human misery. “Very sorry, very sorry” came the reply.

The train was scheduled to arrive at Varanasi at 12:35 AM and get to Gorakhpur at 6:55 AM. It was now 1:30 AM at the Varanasi station, an hour overdue and counting, with no train in sight. But we still considered ourselves lucky - we had, as an act of desperation, asked our hotel manager about any other options for getting to Kathmandu. He said he could get us tickets on that same train but in second class instead of sleeper. Incredulous, I checked online again and found that a couple of higher class tickets had opened up sometime in the last couple of hours. We declined the manager’s offer and booked them directly in order to avoid his 50% surcharge…

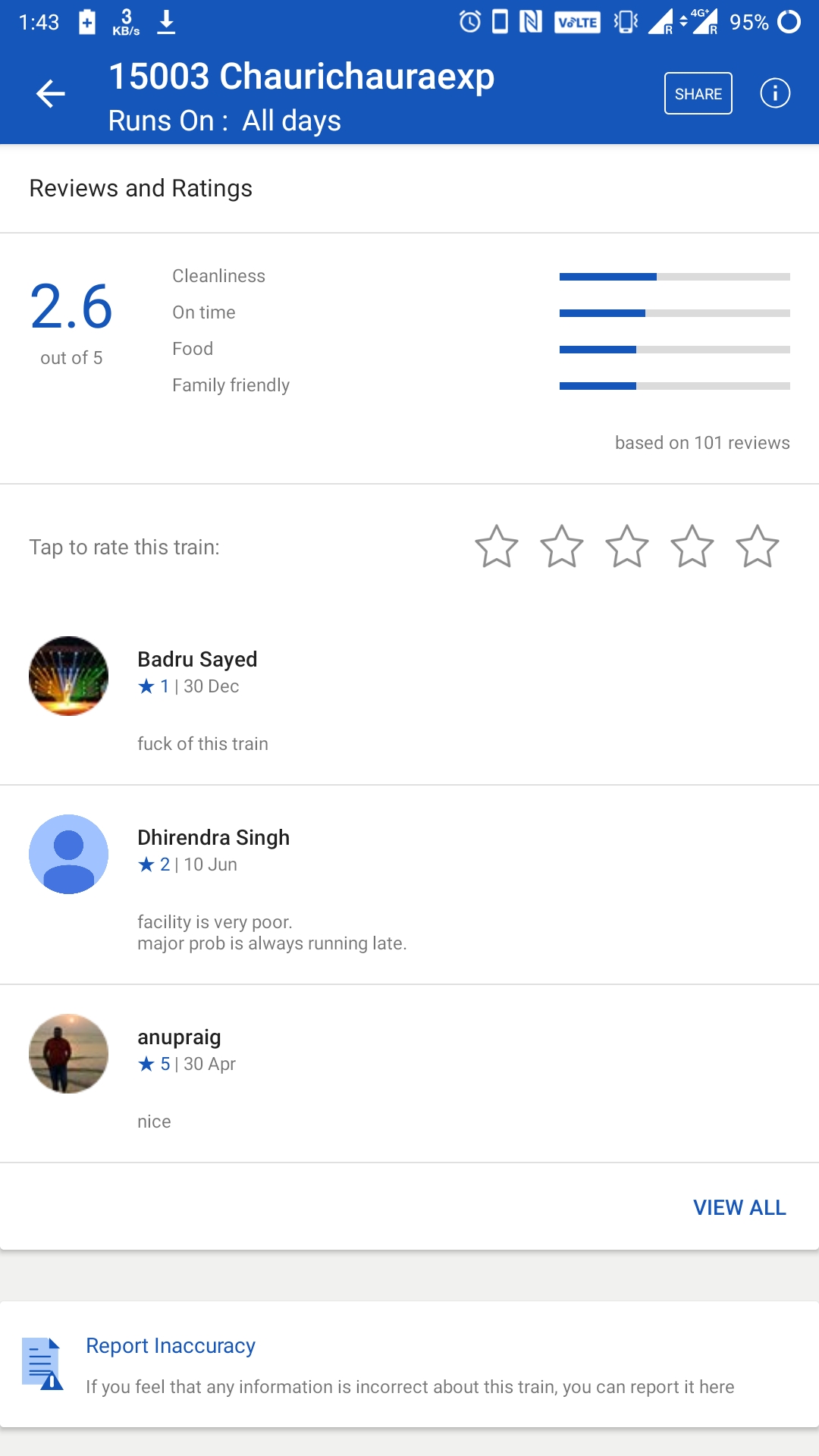

The reviews for our train...

“Max” I said turning to him “I think we need a set of rules for this trip.” He turned to listen, curiosity showing on his face. “Rule number one: no using phones anymore than we have to. It might be thirty hours before we have access to another outlet.” He nodded. “Rule number two: no sleeping at the same time. One of us, or the other, must be awake to guard our stuff. Rule number three: check the estimated arrival time for the train every ten minutes - it keeps changing. Don’t want to be caught off guard.” I paused to think.

“Rule number four!” he said with a grin on his face. “Always more chai!”

I laughed and volunteered to go get the sweet, milky tea this time, while checking the train status billboard.

The train finally pulled into the station at half past two in the morning. The trip hadn’t even started and we were already two hours behind schedule. Max and I wearily climbed aboard and, without discussion, tacitly agreed to break the newly minted rule number two as we both hauled ourselves into the bunks to pass out. Luggage usually doesn’t get stolen in second class.

Waiting for the train.

Sleeping on the train was a little surreal. Your drifted off, feeling yourself being carried in a direction perpendicular to the one you were facing, slipping in and out of sleep as the train softly went thunk thunk thunk thunk thunk over the tracks beneath you…

It was a nice view once the sun came up 😊

We arrived in Gorakhpur at nine. The next leg of the journey was a two and a half hour bus ride to Sunauli, the India-Nepal town where we would walk across the border. We secured a double seat for ourselves and our stuff, and Max went out to scavenge for food as I stayed to guard our things.

I struck up a conversation with one of the few other foreigners aboard the bus. While we were chatting, an Indian teenage girl boarded the bus and started going from seat to seat shaking a pan of coins. It seemed that this was a normal occurrence, as the driver and the other passengers paid very little notice as she made her way down the aisle. Nobody was giving any money and she would only shake the pan for a moment or two before moving on, but my foreign countenance marked me as an easy target. When she got to our seat she planted herself firmly within my field of vision and rattled the pan directly at me with much more spirit than she had done with the Indian passengers.

I know the arguments. Sparing a couple dollars in a foreign country is worth much more to them than it is to us. It’s the foreigner tax. It’s reparations for colonialism. I get it. But I don’t believe in giving money to panhandlers. I have sympathy for these people, but my money is not going to solve their problems long term - only make them more dependent on begging and more likely to hassle other foreigners. Sometimes with children I will try to offer a bit of food I have on hand, but never cash, as children more often than not have older children or adults that they report back to and cough up their earnings.

I tried to wave the girl off, but she would not quit. Instead, she escalated to poking me, steadily, on the arm. Nobody likes strangers touching them and my displeasure showed immediately on my face. I tried to draw back away from the aisle but she pursued me further, finally switching to poking me right on the cheek. I didn’t know what to do. Should I call for help? Should I physically restrain her? Could that get me arrested? Was this a scam where someone else would pretend to be a police officer if I pushed her away? Should I just give her some money or would that make her intensify her efforts? I sat stock still, breathing deeply, frustration coursing through my body. Finally, after a long minute of prodding, she gave up and moved on, stamping her feet in a small fit of anger. The Indians further down the aisle seemed amused by the show and gave her a couple of rupees.

I only sighed with relief when she finally got off the bus.

The jam packed bus.

Max came back onboard with some small bananas and a bag of hard, cashew shaped, processed bread things. I gave him a questioning look and he shrugged - “it was the best I could do.” The bus took off a few minutes later, and we passed some time by telling a story together, one sentence a time, about a small town donkey named Rahul who falls in love with a stripper, but the stripper is selected for the king’s harem, so Rahul has to go and rescue her, and then accidentally knocks her up, before fleeing to go achieve enlightenment on the top of a mountain.

By the time the bus pulled into Sunauli we already knew we had missed our chance at catching the day bus to Kathmandu. So while the natives stampeded off before it had even come to a complete halt we took our time collecting ourselves and trudging out into the scorching, post-zenith sun. Ignoring the constant honking and calls of “Gorakhpur? Taxi to Gorakhur?” we trudged down the side of the dusty, two lane road that served as connection from India to Nepal. “Immigration Declaration BEHIND you 500m” one sign read. “India-Kathmandu border AHEAD 300m” said another. I remembered reading online that the office was “just before” the border, so I set off in that direction, and Max, trusting me to lead the way, followed.

Nepal here we come!

We walked straight under the India-Nepal arch. There were no lines, there were no guards, there was no border control at all. We could have walked right past the Nepalese immigration office and boarded the next bus to Kathmandu with no questions asked - but of course it would have caused problems when we tried to get on a plane out of the country. However, in order to be properly processed with Nepalese immigration, we needed an exit stamp from Indian immigration. But with no Indian immigration office in sight, it was clear that I had led us astray. So we began the fifteen minute trek back the other way…

It's really not a very pretty arch.

“Y’know” I remarked to Max as we waked over the border for the third time, this time our passports stamped and processed appropriately, “according to our passports we don’t belong anywhere right now. We’ve checked out of India but haven’t checked into Nepal… We are in no man’s land.”

“Well we always can get back into America!” he replied.

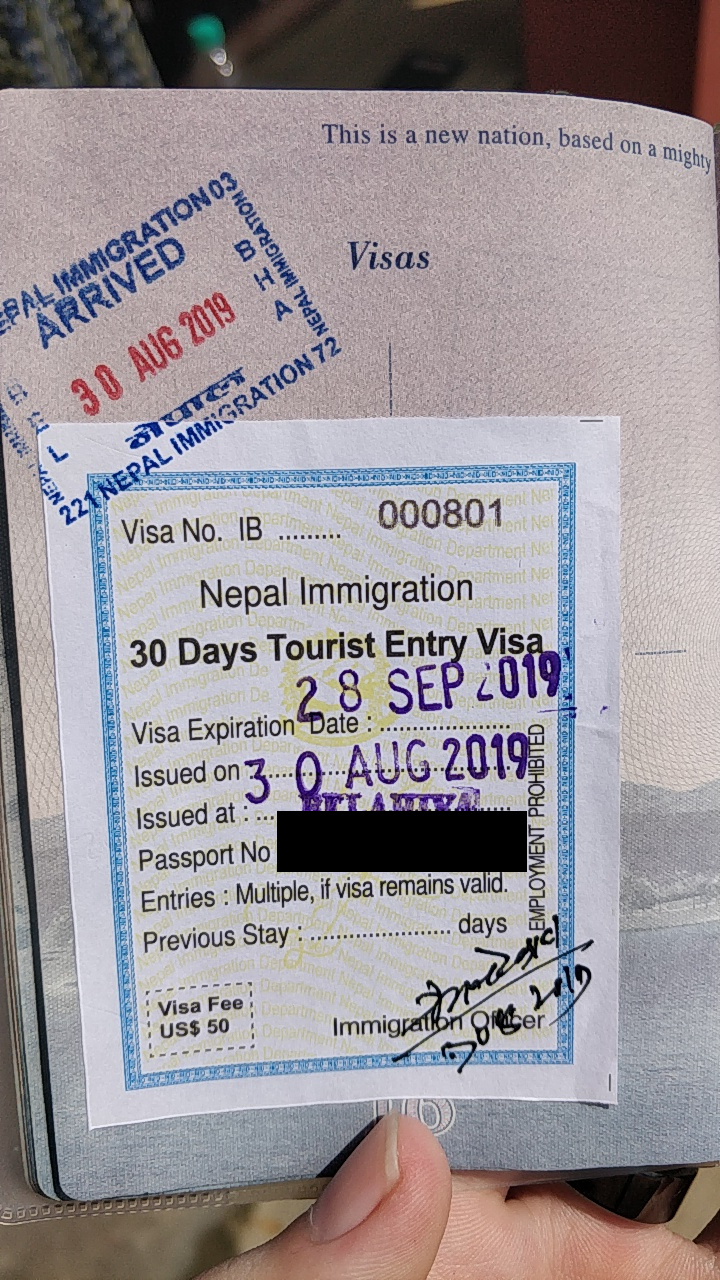

The Visa is on arrival and costs $50 per person - but they only accept bills in pristine condition. We had a close call but the bills that Max happened to have on him just barely passed their inspection.

“THIS IS THE BUS TO KATHMANDU” yelled the man who had just barged into our negotiations with the bus driver. “YOU GO OVER THERE TO BUY THE TICKETS” he continued forcefully, gesturing widely was if we were small children “IT LEAVES AT TWO.”

“WE. KNOW.” my brother bellowed back, before folding his forehead into his hands, too frustrated to continue.

“Look,” I spoke up addressing the newcomer “we know. We’re trying to get our luggage from the two pm bus and buy tickets for the four pm one instead.”

“THIS IS THE BUS-“ he started again, but the Nepali we had just been talking to grabbed him by the shoulders and said something in his ear, unintelligible to us. The loud man shrugged him off and stomped back to where he came from in frustration.

“Ok,” the bus driver said, seemingly finally able to understand what we had been trying to say for the last five minutes, “I give you back your bags and you buy the four pm bus. Ok?”

“Mister look! Mister look!” A Nepalese kid, maybe eight or nine, came running over with his younger sister in tow. He pointed to her ankle, where I could see a small open sore, and then clapped his palms together 🙏 I shook my head, a gesture that actually carries a different meaning in Indian/Nepalese tradition, but he understood all the same. “Mister please!” he exploded, throwing himself onto his knees and grabbing my calf, which were bared in the heat. He started squeezing it alternately, moving up and down the muscle, fascimilating a massage.

“Stop. Don’t touch me” I said, pulling my leg away and walking backwards a step. “Noooo” he wailed, beating on his chest. He crawled forward trying to grab my calf again, and his sister joined as well, fumbling for my other leg with her tiny hands.

“Stop” I reiterated, backing away from them, having no idea what else to do, “Stop.” I had backed myself into the bus, which we had congregated around when it started getting close to departure time, not wanting to get left behind. I turned and climbed up the stairs into the oven that was the interior, sighing in relief when I saw that they were not willing to follow me.

Instead, they turned their attention to Max.

Running over to the other white man, they proceeded with the same song and dance - showing him the same wound he had just watched them show me. But when they started to knead his legs he tried for a less agressive approach, simply crossing his arms over his chest and closing his eyes, hoping they would lose interest when he didn’t respond. Instead, they seemed to interpret the gesture as a dare, and started smacking his body as far up as they could reach with increasing speed and intensity - until after several long moments of me watching with bated breath Max exploded. “STOP” he roared, stepping back and sweeping his arms out. “STOP, stop TOUCHING ME.” The kids backed off, but looked like they were ready to make another approach, until one of the bus company people walked by. “HEY” he shouted at the kids, then continued in loud Nepalese, making a “get lost” motion. They giggled to each other and ran off behind the busses.

I emerged from my stifling fortress into the relative relief of outside, and Max patted himself down. We both sat again, waiting for the bus to show any signs of heading out.

The Bollywood movie had begun again for the third time. I had tried reading, but the mountain roads were far too bumpy to make that possible. Rule number one, the phone ban, was still in effect so I couldn’t listen to music. And, despite my exhaustion, my body was not yet desperate enough to fall asleep inside of what felt like a roller coaster ride up and down the mountain. So instead I just lay, sunk back into the oversized, plushy bus chairs, wrapped in a thin blanket to protect from the sub-arctic AC setting, eyes half lidded, and watched the rather pudgy Indian protagonist sing the intro song for the third time. Every time the bus hit a particularly rough bump the power would go out for a half second, causing the DVD player to reset. However, instead of skipping forward to where it crashed, the uninterested attendant would just play it again from the beginning. Not that I could understand any of the Hindi anyways…

Max started to crack. Curling up into a ball on the seat he rested for a few minutes, trying it out, before switching to a new position. “There’s got to be a way” he muttered to himself as he rotated between kneeling on the floor with his head on the seat, stretching himself vertically across the seat back up and face planted in the headrest, sitting cross legged in a meditation post with his back straight, before finally settling with his back down against the seat and his feet up on the back of the headrest in front of him.

We stopped around midnight for “dinner”. An endless refill of rice and potatoes topped with hot sauce for about $3 - we gorged ourselves and stumbled back onto the bus, finally finding the sweet sweet embrace of sleep.

I woke up as the bus was rumbling down the side of the mountain into the valley of Kathmandu, and peered out across the sea of brightly colored buildings fighting valiantly against the dismal gray sky above. Max was still passed out in the seat next to me, breathing gently under the coat that he had covered his face with sometime during the night.

After pulling into the parking lot and gathering our belongings we hooked up with the two other foreigners on the bus to see if we could all split a taxi to the hostel district.

A wet and cloudy welcome.

“Look it’s good money” the young Italian man told the taxi driver. The driver eyed the four of us skeptically. He clearly thought he should be able to get more than ₹500 ($4) a head, especially in the drizzling rain, but seemed to think better of trying to negotiate in English. He waved us into the car, and after filling up the trunk to the brim we piled in with our extra luggage on our laps, dripping onto our already damp clothes. I gave the driver the address of the hotel I had booked online, and watched streets pass by with bleary eyes, already dreaming about the soft bed that awaited me…

“So are you looking forward to your meditation retreat?” my girlfriend asked over our video call. “Jeez” I said, rubbing my eyes, still tired even after a four hour nap, “after what I just went through I feel like I’m ready for anything!” Little did I know how wrong I would turn out to be…

Dad says:

This was well written and entertaining, but I don’t think I want to visit India now.